Why You Should Draft Your Quarterback Late. Every Single Year.

A Week 17 contest in 2011 between the Lions and Packers will forever be remembered as Matt Flynn Day. The backup quarterback threw for 480 yards and six touchdowns – something that’s been done only three times in NFL history – which led to a $26 million contract with the Seahawks in the subsequent offseason.

But what often goes unnoticed in that game is the fact that Matthew Stafford, a third-year quarterback who had yet to live up to his first-overall draft cost, threw for 520 yards. As a result, a quarterback who had struggled with injury and inaccuracy through his freshman and sophomore years in the league found himself with over 5,000 yards passing on the year.

Prior to the start of Stafford’s third season, the 5,000-yard mark had been hit by only two quarterbacks in NFL history. You’d think the Detroit quarterback’s 5,038-yard campaign would be a big deal. But it wasn’t. He was one of three quarterbacks to reach the historic number that season, with a fourth, Eli Manning, just 67 yards behind.

To say the 2011 season was historic would be an understatement. We had never seen such a disparity between these elite quarterbacks in fantasy football versus the rest of the field. Throwing 700 times in a single season or tossing 45 touchdowns to only 6 interceptions was only done in Madden.

In 2011, it was real life.

Explaining why this happened would be mostly speculation (personally, I think a lot of it had to do with the near-lockout), but one thing was certain: it changed the way people viewed quarterbacks in fantasy football.

At that point in time – the end of the 2011 season – I hadn’t done a lick of fantasy football writing. Drafting a quarterback late was a regular part of my fake football strategy, and the approach, to my naïve self, was such an obvious one.

Fantasy football is a numbers-driven game that deals with really basic market-like principles. To me, it was clear that you devalue the quarterback and tight end positions in the game – you’re only starting one of them each week, they get drafted later than running backs and wide receivers, and as a result, they’re easily attainable off the waiver wire when you need them.

But after 2011, that type of logic was thrown out the window. Aaron Rodgers and Drew Brees became full-blown first-round fantasy draft selections, while Matthew Stafford and Cam Newton crept into Round 2.

I no longer assumed people saw what I saw with the quarterback position in fantasy football. So I wrote a book, and appropriately named it The Late Round Quarterback.

The truth is, owners overstate change in real football as it equates to the fake game. While these elite quarterbacks are posting absurd numbers, so is almost every other signal-caller in professional football. Let’s start there.

The Unchanging Game of Fantasy Football

The NFL is going to evolve. It’s going to change. But do you know what won’t? Fantasy football.

Before you start talking about your home two-quarterback league, or the one where you get 14 points per touchdown pass, realize that the majority of leagues are still starting one quarterback, and those quarterbacks are still getting four points per touchdown pass. And because of this very fact, the late-round quarterback strategy has almost zero exceptions.

Most people see this, but still believe player projections can trump the notion. In other words, seasons like Peyton Manning’s 2013 can alter the way you approach the strategy.

Thinking in hindsight is easy though. There’s a reason Peyton Manning was selected towards the end of the third round in drafts last year. It’s because we didn’t predict a superhuman season. Creating a strategy in retrospect can get you into a lot trouble.

Fantasy football is a supply and demand-driven game. Forget fantasy points and scoring for a second and focus on roster construction. You’re starting double – sometimes triple – the amount of running backs and wide receivers as you are quarterbacks and tight ends. You need players at those positions more. There’s a reason average draft position data, each year, show those two positions being selected repeatedly at the beginning of drafts. It’s not because they’re fun or easy to predict – it’s because they’re necessary.

While quarterback is the single-most important position on a football field, it’s not in fantasy. This supply and demand way of thinking shows just that – there’s a ripple effect that spreads to so many areas of fantasy football because the demand for the quarterback position is so inherently small.

One of those things is cost. Because the demand for quarterbacks is so small, it allows usable players at the position to drop in fantasy drafts. In fact, since 2006, the 12th quarterback, on average, has left the board in the middle of the eighth round. In a 12-team league, that’s the last hypothetical team starter. The 24th receiver – remember, your 12-team league is starting at least two of them – has typically been selected at the beginning of the sixth, while the 24th running back gets drafted in the middle of the fifth.

Your draft isn’t necessarily going to go that way. But a lot of you are also probably going to overstate what happens in your draft.

I often get the question, “But what if everyone goes quarterback early – do you still wait?” My answer is a resounding yes, as you should use your early picks for positions that are in higher demand. If six people go quarterback in the first round, all they’re doing is forgoing the opportunity of having a top-tier running back or receiver. More on that later though.

I also hear, “But what if everyone drafts their quarterbacks late?” That, to me, is the more interesting question, and one that leads to an answer so important that I felt the need to bold it. The key to the late-round quarterback strategy is not to simply draft a quarterback late, but to be flexible and understand value.

The reason the late-round quarterback strategy is a thing is because it’s based on what happens in nearly every single draft. When you have an outlier, things can change. But that’s the case with anything you do. Just remember that this isn’t a game a chicken – this is a game of value.

Value Based Drafting Can Be Misleading

Back in the fantasy football stone age (which, you know, was like a little over a decade ago), Joe Bryant – an awesome man and respected industry leader – coined the idea of Value Based Drafting, or VBD. The principle of the strategy is pretty straightforward: “The value of a player is determined not by the number of points he scores, but by how much he outscores his peers at his particular position.”

This is accepted knowledge in fantasy football at this point – you don’t compare how Aaron Rodgers performs against Adrian Peterson. You evaluate how he plays versus how Ben Roethlisberger, a quarterback, plays.

The foundation of VBD is one that everyone should embrace – you compare point differentials within positions, not across positions.

However, there are general issues that I have with VBD. Not only with how we all use the system, but how we’re rather hypocritical with the concepts Bryant pushed forward so many years ago.

With Value Based Drafting, you make projections at the beginning of a season, and judge the value of a player based on how well his projections look versus a “baseline” player. The baseline player itself shifts depending on league construction, and that can sometimes be a difficult thing to truly comprehend, especially given natural injury tendencies at particular positions.

But aside from the baseline issue, VBD irks me a bit because of three things. First, it assumes your projections are correct – there’s no variance built into it. If I’m wrong on who I project to be a first-rounder, and I don’t weigh in the potential risk, I’m screwed.

Second, VBD deals with yearly projections. Now, there’s nothing wrong with cumulative, year-long statistics, because they can certainly give you a good picture about a player. But they don’t always tell you the entire story. If a guy gets 50 percent of his season-long production in one game, does that really help you? Chris Johnson owners know exactly what I’m talking about.

Lastly, traditional VBD – and this has been amended since – doesn’t factor in market value. And during a time when we have average draft position data everywhere, that’s pretty important, especially when, as I noted earlier, you can get baseline quarterbacks far later than running backs and wide receivers.

But aside from my skepticism, what I’ve found interesting is how fantasy owners have adopted this idea only for fantasy points scored. In other words, the high-level notion of comparing within and not across positions is only being analyzed in terms of projections or how many points a player is going to score.

What about bust rates?

Though I’m not typically a fan of season-long data, I recently did a study analyzing bust rates of both running backs and wide receivers in fantasy football. Bust rates, in essence, measure how well a position performs given preseason expectations. Without getting into too much detail (I’ll talk more about it later), the general notion of the two articles was the same: early-round running backs and wide receivers do bust at a high rate, but they bust exponentially more as you approach the sixth round and beyond of your 12-team draft.

To put this another way, if we were to approach bust rates like we do standard Value Based Drafting, we’d find more value in running backs and receivers than we would otherwise. After all, the reason folks are shying away from backs and receivers isn’t so much VBD related as it is bust rate related. Rather than simply looking at how those positions bust at the beginning of drafts and moving on, we really should look at how these bust rates compare within the position to see how valuable those players actually are.

But like I said, fantasy owners, unintentionally, can be hypocritical. I certainly am at times, too. We can’t – and shouldn’t – view things one way and not use that same process with another aspect of the game.

This, too, occurs with how you approach the game from a weekly perspective. You do play it from a weekly perspective…right? Well then why are you using season-long projections to justify your stance?

Weekly Production and Predictability Matters

Last season, Andy Dalton finished as fantasy football’s fifth-best quarterback. At season’s end, he was better than Matthew Stafford, Philip Rivers, Colin Kaepernick, Russell Wilson and Tony Romo. He scored about four points fewer than Andrew Luck, and was just nine points off of Cam Newton.

To me, Andy Dalton wasn’t even close to the fifth-best quarterback in fantasy last year.

Dalton finished as a weekly top-12 quarterback last season just six times, excluding Week 17 since it’s worthless to fantasy football. While that number seems a little arbitrary – and it kind of is – a ranking in the top-12 at the position represents a QB1 in a 12-team league. Eight quarterbacks had more weekly top-12 weeks than Dalton did, and an additional five had just as many.

Dalton made a living off of monster weeks. Of his top-12 performances (usable weeks), he finished second three times, third once and fifth once. The last “usable” week saw him finish 11th.

This is no exact science, don’t get me wrong. A player could consistently finish as the 13th-ranked quarterback and come out looking poor in terms of usable weeks. But in general, looking at fantasy football from this perspective can give you a glimpse of how a player actually performed because, in the end, fantasy football is a weekly game.

If you’d like to read more on this particular subject, take a look at Rich Hribar’s work over at XN Sports, reviewing the position in 2013 from this angle.

Replaceability

This notion of looking at weekly usable weeks versus season-long statistics can drastically change the way you view lineup slots in fantasy football. This is mostly because you begin to see how replaceable positions truly are.

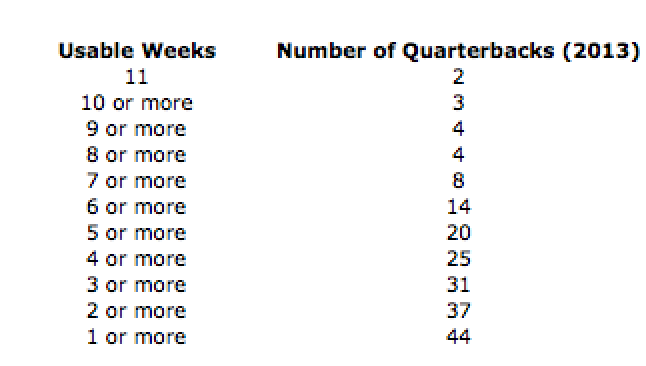

A 12-team league starts 12 quarterbacks each week. In 2013, 44 different quarterbacks had at least one top-12 week, excluding Week 17 (remember, these are called “usable” weeks). And no, that’s not a typo – 44 different guys hit the mark. In terms of top-6 performances, or “elite” weeks, there were 33 with at least one.

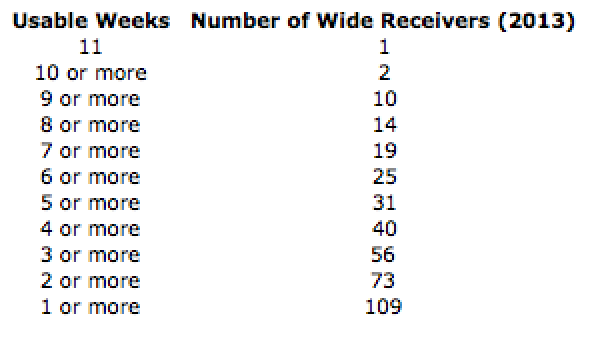

It doesn’t just stop there. Take a look at the tables below.

The numbers above shouldn’t mean a ton yet considering we’re looking in a vacuum. We still need to compare them to other positions. But what’s pretty surprising, without the context, is how many freaking quarterbacks matter in fantasy football. That, and how close each quarterback performed to one another.

Keep in mind, too, that the data above includes the most historic season in quarterback history. Even still, Peyton Manning had just one more usable week than Matthew Stafford (10), and two more than Andrew Luck (9). And, for giggles, he had just four more than Alex Smith (7).

Manning was so valuable though because 9 of his 11 usable weeks equated to elite ones. That was two more than Nick Foles, who finished in second with seven.

However, Peyton’s 2013 campaign is a true outlier. If you look at Drew Brees, who consistently finishes as a top-two fantasy quarterback year after year, you can start to understand why the quarterback position is replaceable.

Last season, 11 of Brees’ 16 relevant fantasy football weeks equated to a top-12 finish. That, as you can see, was as good as Peyton Manning. Awesome. Neat. Great. Drew Brees was a consistency monster.

But Drew Brees also finished with five elite performances, the same number as Andy Dalton and Cam Newton. That was one more than what we saw from Alex Smith (there’s his name again), too.

Four of those five games resulted in the top rank at quarterback in a given week. That’s pretty impressive, no doubt. Those four games averaged out to be 32.34 fantasy points, with each game ranging from 31.68 to 33.18 points.

But look at Andy Dalton, sitting there with his orange hair and new contract, waving his hand saying, “But I did that too!” After all, a player ranking fifth in cumulative points had to have had some monster weeks, right?

Dalton’s top four games saw an average of 30.06 points, just three fewer than Drew Brees. Yes, you’re reading that correctly – Drew Brees’ best games last year were barely better than Andy Dalton’s best.

The difference is that Drew Brees consistently will break the top 12. While Andy Dalton was a “boom or bust” player, Drew Brees was a “boom or good” player.

And while you may think Andy Dalton’s weeks weren’t predictable, we’ll get to that later.

In general though, I think this is the problem and misconception with early-round quarterbacks. They mostly put up unbelievable cumulative statistics because they’re consistent from week to week. But their ability to post truly elite performances isn’t as good as you may think.

And while Peyton Manning’s 2013 season is definitely the argument in favor of going quarterback early – his elite performances were truly unmatched at the position – let’s remember that it was the best quarterback season of all time. And let’s also not forget that no one saw it coming, as Manning was a third- or fourth-round selection entering the season.

You’re probably now wondering how this compares to running backs and wide receivers, as these are the positions you’d be opting for instead of an early-round passer. I’ll ignore tight ends just to keep things concise, but if you’re interested in a pro-late-round tight end argument, give Episode 37 of Living the Stream a listen.

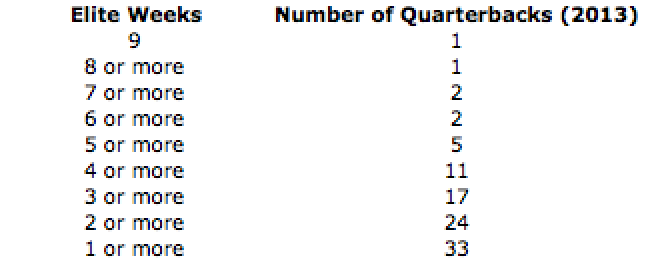

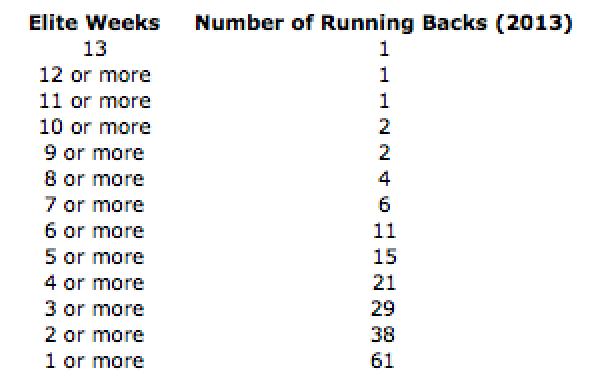

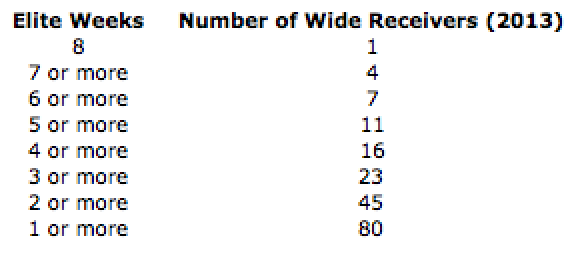

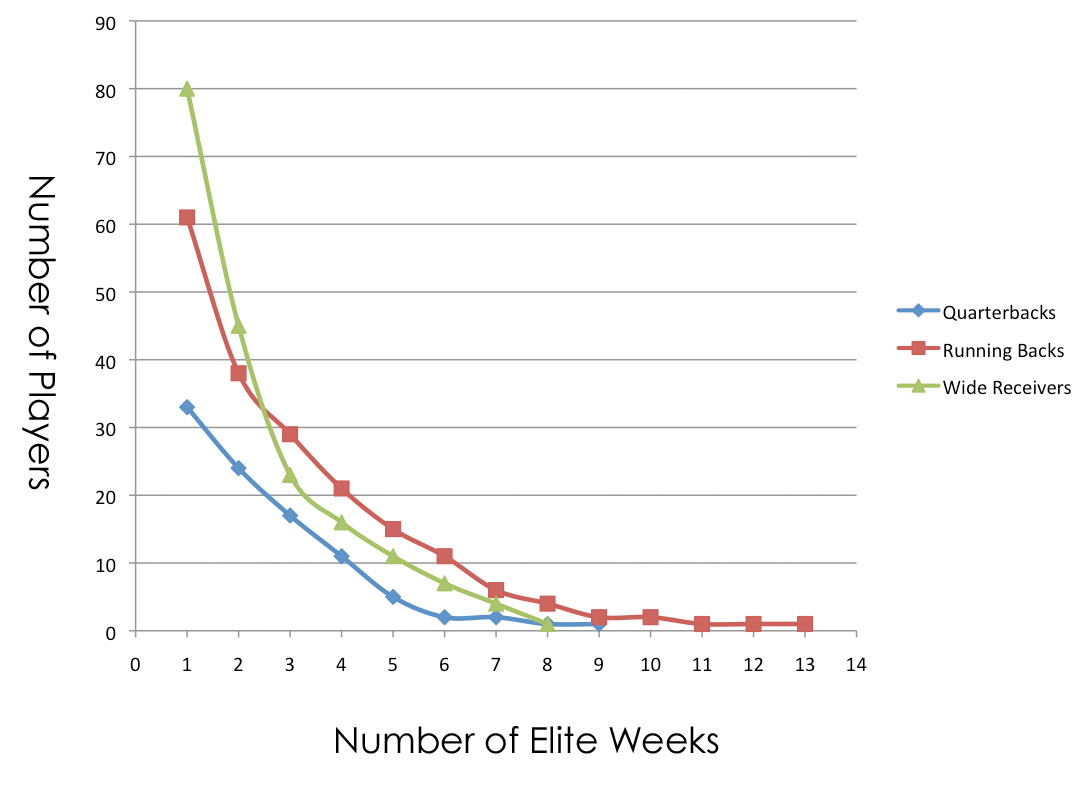

The chart below depicts usable and elite performances in 2013 at running back and wide receiver. Keep in mind that a usable week at these positions equates to top 24, while an elite one is top 12. Why? Well, because you’re starting at least two (usually more) in a 12-team league, driving up the number used each week.

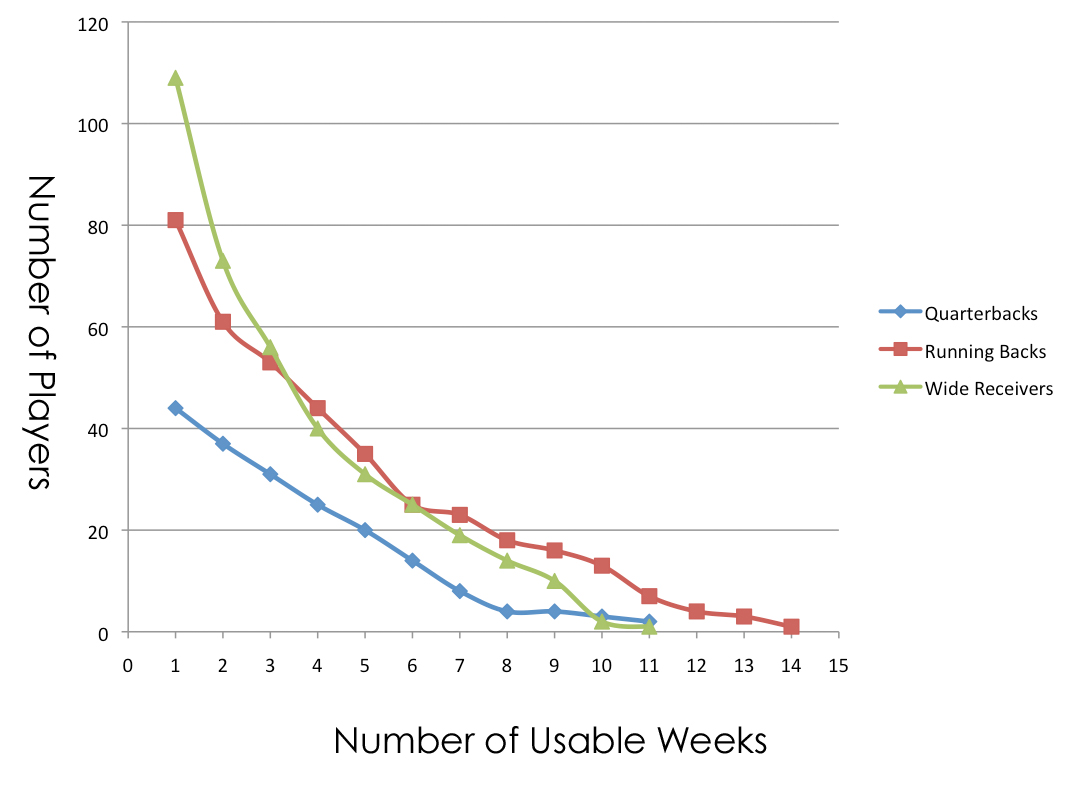

This is a lot of data to take in, so before we get into the details, it’s probably best to see the numbers in a more visual form.

The graph above shows us the number of usable weeks from each position on the x-axis, with the number of players hitting a particular mark on the y-axis. What I want your eyes to first focus on is the left side of the graph, where we’re not looking at the elite players like Jamaal Charles, Josh Gordon or Peyton Manning.

What you notice in the three lines is that the drop-off from one group of quarterbacks to the next is almost completely linear until you hit roughly the 8 usable week tally. Because so many running backs and wide receivers get at least one or two usable weeks, you’ll notice a sharper drop towards the left side of the graph, as it slowly but surely levels off as you approach the elite guys.

This is important. The consistent slope of the quarterback line shows that there’s little advantage from one tier of quarterbacks to the next. As you move from group to group, you’re not gaining much.

This isn’t the case at running back, and this is even more exaggerated at wide receiver. Why? Because lots and lots of running backs and receivers are relevant in a week or two during the fantasy season, but only a handful of them can consistently perform week in and week out.

If you do some simple math with the tables above, you see just that. The quarterback position starts with 44 of them obtaining at least one usable week, and that moves to 37 when you move to two – a decrease of seven. From two to three usable weeks you’re dropping by six, and this is consistent all the way down. The drop off is almost perfectly linear.

That’s not the case for running backs and wideouts, and, again, that’s essential. It shows us that there’s a clear separation between the higher-end players versus the bottom-end ones, whereas at quarterback, the dip is consistent. There’s no drastic gap in tiers.

This, ladies and gentlemen, is the idea of replaceability. It’s far easier to replace quarterback production from a week to week standpoint than it is running back and wide receiver, despite many running backs and wide receivers being worthwhile in one or two weeks during the season.

The same type of conclusions can be drawn from the elite graph from 2013 as well.

There are now two questions a doubter should be asking. The first is, “Well, don’t we know who those elite quarterbacks are going to be, while running backs and wide receivers bust at a higher rate?”

Good question, early-round quarterbacker. We’ll get into this in the next section.

The other question relates back to the Andy Dalton and Drew Brees example above. “Hindsight is easy, but how was I supposed to know to start Andy Dalton during his blow up weeks?”

That answer, my friends, lies in position predictability.

Predictability

We know that quarterbacks are more replaceable than wide receivers and running backs, but the player doing the replacing doesn’t really matter if you can’t predict how he’s going to perform in a given week.

Let me run through an example. It’s Week 7, and you’ve got Ben Roethlisberger as your starting quarterback. You’re not super into starting him that week because his matchup sucks, and you see Ryan Tannehill chilling in free agency with an upcoming game against the league’s worst pass defense. Instead of playing your typical quarterback starter, Ben Roethlisberger, you drop a guy who’s collecting dust on your bench, and plug Ryan Tannehill into your lineup.

Does he perform well? That’s the hope. Will he perform well? The odds aren’t as bad as you’d think.

If you’ve visited this site to listen to the Living the Stream podcast, you understand what the concept of streaming is all about. For those unfamiliar, streaming is a fantasy strategy where you play your quarterback (tight end or defense, too) based on matchup, not just because “he’s your starter”.

In other words, you’re not locked into starting the same passer each week of a fantasy season (another reason why season-long projections are misleading), and in order to maximize the point output at the position, you play the quarterback with the most attractive matchup entering the week, whether he’s on your bench or off the waiver wire.

First and foremost, before I go on, your goal entering a fantasy draft shouldn’t necessarily be to stream. I look for players with upside late, and hope that player becomes a top-five passer on his own. But as a fall-back plan, streaming is mighty, mighty effective.

You can stream quarterbacks, tight ends and defenses because they’re “onesie” positions – each team in your lineup is starting just one of them in a given week. As a result, the positions are in lower demand, giving you more usable assets in free agency. If it’s a league with deeper rosters, you could almost consider the streaming approach as a platoon one, where you own a couple of middling quarterbacks and play them by matchup each week.

I know how terrible this sounds to someone who’s never even thought of this approach. Crazy, erratic and miserable, right? Not exactly.

A year-and-a-half ago, Pro Football Focus’ Pat Thorman put together an unbelievably telling article about roster maximization in fantasy football. In it, he compared three groups of quarterbacks using 2012 data – QB1-10, QB11-20 and QB21-30 – and showed the group of quarterbacks’ production versus top half and bottom half defenses.

According to Thorman’s study, top-10 quarterbacks scored an average of 19.8 fantasy points per game against top half defenses, and 21.6 points against bottom half ones. The group’s average points per game was 20.7.

The next group of passers – quarterbacks ranked 11th through 20th – saw an average of 16.2 points per game, regardless of the defense that was faced. But much of this average had to do with a low score against top-half defenses. This middle group of passers scored 13.1 points per game against the good defenses in the league, but 19.0 against bottom half ones. That 19.0 score was just 1.7 points away from the average points per game you’d find from a top-10 quarterback in 2012.

The final tier of quarterbacks saw a 14.6 points per game average, but against bottom half defenses, the average jumped to 16.4.

This high-level look shows you something that’s very important: consistency at the quarterback position – at an individual level – doesn’t really matter.

How effective can streaming your quarterback – a backup plan – be in fantasy football? Let’s look no further than my lovely Living the Stream co-host himself, Denny Carter, and his series on 4for4.com last season.

In a fantastic group of articles, Carter documented his quarterback streaming picks each week. And these guys weren’t players like Ben Roethlisberger and Russell Wilson – Carter used quarterbacks like Josh McCown and Carson Palmer.

In the end, his Frankenstein of a quarterback ended up scoring an average of 17.7 points per week. In total, Denny created the equivalent of a QB5 through playing the waiver wire.

Denny’s a smart guy who understands fantasy football just as much as anyone in the industry. So while you may credit his streaming success to his incredible understanding of the game, like Thorman’s findings above, Denny’s experience is powerful.

This is probably a good time, too, to point out that elite quarterbacks don’t always finish as elite quarterbacks. Remember that Aaron Rodgers guy last year? Yeah, he missed seven games due to injury – running backs aren’t the only ones who bust for health reasons, folks.

How about Tom Brady a season ago? He was being selected as the fourth quarterback at pick 38, according to MyFantasyLeague.com. He finished as fantasy’s 14th-ranked passer, reaching the weekly top 12 at the position fewer times than Alex Smith (Remember him?).

In 2012, Matthew Stafford was a second-round pick. He finished as the 11th-best quarterback, behind rookies Russell Wilson, Andrew Luck and Robert Griffin III.

Considering only three or four passers are being drafted so early, let’s not pretend that a perceived elite quarterback at the beginning of a fantasy season is going to finish as an elite quarterback at the end of one. It doesn’t happen automatically, as many people make it seem.

And the main reason people see lower bust rates at quarterback is because finishing 13th or 14th at the position looks, at a quick glance, as nothing major. Sure, you invested an early-round pick, but it’s not as though he busted that much, right?

Well, considering how replaceable the position is – I hope you realize this by now – a 13th-ranked quarterback really isn’t doing much for your fantasy team. Denny used waiver wire pickups and compiled a fifth-ranked quarterback! Why would you feel good about getting Tom Brady early last year?

The reason Denny was able to stream so effectively is because the quarterback position is the most predictable of any of the big four in fantasy football (quarterback, running back, wide receiver and tight end). You can click that link and see some math behind it, but if you’d rather just read something based on logic, here goes.

Quarterbacks throw a lot of passes. All of them too, not just the elite ones anymore. In fact, 30 of the 32 teams in the NFL last year dropped back to pass 500 or more times. That’s 31.25 drop backs per game.

With more volume comes more opportunity. And with more opportunity comes a larger sample size to draw from. In turn, the position becomes easy to predict each week before games are played.

If you reference the article, you’ll find that running backs are the second-most predictable position. That’s because most backs have foreseeable per-game volume numbers, and they’re not directly reliant upon quarterback play.

Wide receivers are, which is a huge reason we see variance at the position. Even as you look at the usable and elite week charts above, you see that there are a lot of useful wideouts during a fantasy football regular season. The problem is that the majority of those weeks simply aren’t predictable, which is why elite wide receivers matter a lot in fantasy football, despite them sometimes not looking great from a value over replacement analysis perspective.

Naturally, tight ends are the least predictable because they’re simply not running routes at the same rate wide receivers are.

This is why streaming can work. And given the depth at the quarterback position, and the fact that so many teams are throwing a high number of times each week, it’s not an overly difficult task to pinpoint quarterbacks – waiver wire ones – each week who are facing easy defensive matchups.

But again, the goal to drafting a quarterback late isn’t necessarily to stream. However, the position is more predictable than any other, and if your late-round passer doesn’t pan out as a weekly starter, you’ll be just fine.

There’s Always a Cost

I’ve argued with every sort of fantasy owner about the late-round quarterback strategy. And every single one who would take the early-round signal-calling approach to their grave tells me the same thing: You just can’t match the production of an elite quarterback if you don’t get one.

Well, that’s not exactly the point. Sure, you can get a top-notch passer early, hit on a couple of running backs and wide receivers and have a team that’s quite literally impossible to stop. But that’s usually not how it works. At least, that’s not a sustainable, long-term way of winning.

Process over results, people. You snagging Josh Gordon in Round 8 last year has nothing to do with you being able to pinpoint elite late-round talent. How do I know this? Well, because there are plenty of reasons another team could’ve had Gordon instead of you, and for every Josh Gordon, there are about a dozen Kenny Britts.

I’m fully aware that the chance of my quarterback performing like Drew Brees this year is slim. But my chances to outscore the wide receivers and running backs on the team with Drew Brees is great.

We can’t forget that fantasy football isn’t just about the players you draft, but the players you don’t draft as well. When it’s your turn to make a choice in the second round, and you opt to get Drew Brees, you’re missing out on high-end running backs and receivers. And while you’re avoiding those positions because of their perceived bust rates, I’ll remind you again – the bust rates of these positions early in your draft are far more favorable than what you’ll find even in Round 5.

This is opportunity cost – the loss of potential gain from other alternatives when one alternative is chosen.

Opportunity Cost

Let’s pretend that it’s the second round, and you select Aaron Rodgers. Your reasoning is that he’s far and away the best quarterback projected, and will give you a weekly edge as a result. (Clearly, given the stance on week-to-week numbers trumping season-long ones above, I’d make fun of this person in a draft room.)

Little does this owner realize that he decreased his odds in obtaining a WR1 or an RB1 dramatically. If you recall, I referenced the bust rate articles that I wrote over at numberFire above. Now I’m going to dig into those a bit more as it pertains to opportunity cost.

According to FantasyFootballCalculator.com, we’re seeing running backs ranked 7th through 12th leave the board in Round 2. Conveniently, in my bust rate article, I broke down this running back demographic.

Over the past five years, running backs with an average draft position of RB7 to RB12 – according to MyFantasyLeague.com data – have finished as RB1s (top-12 running backs) 46.67% of the time in PPR leagues. That seems pretty terrible, but backs ranked 13th to 18th – third-round runners – have a 30% rate of hitting RB1 territory.

In other words, if you’re only option outside of Rodgers was to go with a running back, your selection of the Packers’ quarterback decreases your chances of obtaining an RB1 in the following round by about 17%.

Mind you, the RB7-12 group versus the RB13-18 one has a similar hit rate, in general, if you were to consider a “hit” as a running back ranked first through 24th. But what the bust rate data shows is that, despite folks hating on early-round running back choices, getting one in the second round still yields much, much more upside. And, as we saw in the replacability charts above, having that running back upside is huge.

The issue is that running back isn’t the only position you’re losing out on. Wide receivers are going a tad earlier than usual this season due to the perceived risk in drafting early-round running backs (or the Recency Bias fantasy owners are using due to last season’s poor showing from backs), but three or four top-six wide receivers will traditionally fall into the second round of a fantasy draft.

Top six wide receivers are brilliant in terms of consistency. According to the wide receiver bust rate study, 73.33% of top-six wide receivers finish as top-12 ones at season’s end. Their median rank is six, which is five spots ahead of what you’d see from an elite running back. When you shift to WR7 to WR12, this median rank drops to 17.5. And when you move to WR13 to WR18, it drops even further to 24.

And again, remember the weekly usability and elite graphs in the section prior to this one? You know, the one that showed a drastic, sharp decline in worthwhile weeks from wide receivers prior to getting to the elite ones? Yeah, that advantage is gone if you forgo the position early.

Elite wide receivers matter, and getting a quarterback early often times means that you won’t be getting one of these players, at least according to average draft position data (and casual leagues).

And even if you do decide to go with a wide receiver first and a quarterback second, now your top running back has, as noted, just a 30% chance of actually finishing as a top-12 back if you get one in the third. And that only will get worse from your RB2 spot, even if you were to draft one in Round 4.

It’s incredibly true that early-round quarterbacks don’t bust as much as these other positions do, and to many, that’s one of the advantages in getting them. Among quarterbacks ranked first to third over the last five years, 80% have finished as a high-end QB1 (top-six quarterback). The QB4 to QB6 range sees a dramatic dip to 33.33%, which only strengthens the point of top-notch consistency at the quarterback position.

But as I showed with the replaceability and predictability section above, quarterback consistency at an individual level really doesn’t matter. The game’s played on a weekly basis, not a yearly one. It’s not as though you can’t change the player being started in your quarterback spot each week.

What’s more important, however, is the general cost of a quarterback in the game of fantasy football.

This is where things come full circle.

I talked about supply and demand earlier in the article, noting the quarterbacks will drop in drafts because the demand for the position is small. As a result, the position is quite cost-effective.

And with more quarterbacks being usable in fantasy football due to the high volume of passes each team is throwing, the notion of “last starter selected” is becoming more and more irrelevant.

Think of it this way. The 12th quarterback being selected in fantasy drafts right now is Tony Romo, and it’s happening at the end of the 8th round. That, according to FantasyFootballCalculator.com, is six rounds after Drew Brees and Aaron Rodgers are being drafted (Manning is a late-first rounder).

Typically you’d look at that and say, “Woah, that’s a lot of equity to be had considering the running backs and wide receivers at that point in a draft are literal dart throws.” No, seriously – the chance of you hitting on a back or wide receiver that late is incredibly, incredibly small. That’s all in the bust rate charts linked above.

The funny thing though is that the eighth-round territory is probably still early to take a quarterback in today’s NFL. Given the replaceability of the position, the fact that streaming is more-than-viable and that finding elite talent at wide receiver and running back is difficult, there’s actually little reason to get a guy like Tony Romo in the eighth.

The truth is – and hopefully you concluded this as well from the graphs shown in this article – there’s not a whole lot of variation between middle-round quarterbacks (Rounds 6 to 10) and late-round ones (Round 11 to 14). The biggest difference between the two types – aside from opportunity cost – is the tendency to become full-blown, top-notch passers. But even then, the lovely Denny Carter showed that doesn’t even matter.

Shouldn’t everyone be doing this?

It’s Not an Exact Science

The general issue with any strategy is the fact that it’s not perfect. Plenty of teams are going to win in 2014 with Peyton Manning on their roster, while others who select Ben Roethlisberger in Round 12 are going to wish they had never played fantasy football in the first place.

The important thing to remember is that a fantasy football draft isn’t what wins fantasy football. It’s a part of it – a big part of it – but there’s plenty of other aspects to the game that are just as important. The reason we focus on the draft so much, quite frankly, is because we have so much time to focus on the draft.

But in-season decisions, waiver wire adds and trading are all part of the equation as well. This is just a piece to the puzzle.

Confidently, I say that drafting your quarterback late is the best strategy in fantasy football. And the best part is that it still doesn’t necessarily interfere with some other fantasy notions out there, like Shawn Siegele’s Zero RB method. In fact, Shawn’s findings match up with the bust rate study I performed – if you’re not going to go running back early, you might as well not go running back at all.

We’re seeing the masses accept the fact that quarterbacks are inherently devalued in fantasy, as leagues shift to superflex and two-quarterback leagues. I’m all for that – it shows true progression in a game that’s been unchanged for some time.

But until that’s the norm, I’m going to continue to exploit the system. And I’m going to continue to win.